John Mark Hicks recently po sted some material on the Lord’s Supper that’s very pertinent to this series, which I thought I’d wrapped up a few weeks ago. The post summarizes a scholarly paper he presented at the 2010 Stone-Campbell Conference.

sted some material on the Lord’s Supper that’s very pertinent to this series, which I thought I’d wrapped up a few weeks ago. The post summarizes a scholarly paper he presented at the 2010 Stone-Campbell Conference.

He writes in the post,

Given the following assumptions, some time during the early to mid second century the Eucharist was separated from the Agape. My assumptions are:

- There is a consensus among New Testament scholars that the Eucharist was originally conducted in the context of an Agape

- There is a growing consensus among New Testament scholars that the table of the early church in Acts is a continuation of the table ministry of Jesus and particularly a continuation of the post-resurrection meals of the disciples with Jesus before his ascension.

- There is a consensus among New Testament scholars that the Agape was a frequent and common phenomenon in early Christian communities.

- There is a consensus among church historians that the Eucharist and Agape were still linked if not identified with each other at the beginning of the second century, especially in Syria.

- There is a consensus among church historians that the Eucharist and Agape were not only clearly distinct but temporally separated at the beginning of the third century. Clement of Alexandria (Instructor 2.4.3-4; 2.6.1-7.1), Tertullian of Carthage (Apology 39) and Hippolytus of Rome (presuming his primary editorship of the Apostolic Tradition 4, 25-27) each distinguish the Eucharist from the Agape.

In the paper, he writes,

The Eucharist is deeply embedded in the Jewish world. It is not only a Passover meal but also the “breaking of bread” reflects the traditions of weekly Sabbath meals (e.g., Acts 20:7) as well as the thanksgiving sacrificial meals of the Torah (e.g., 1 Corinthians 10:16-17). This is particularly seen in Syrian Christianity where the influence of Judaism is widely recognized among scholars.[22] The Eucharistic prayers of the Didache are certainly Jewish in character as it is a rendition of the Jewish berakah.[23] …

As the church progressively moved away from its Jewish roots, it lost the significance of the religious meal as meal and reduced the supper to bread and wine within an altar metaphor rather than retaining the overarching table metaphor. Syrian or Oriental churches retained the sacral world of Jewish meals which was lost in the Greek and Roman parts of the Empire. …

[T]he loss of the Jewish roots of the Last Supper and the “breaking of the bread” in Luke-Acts throughout the Mediterranean basin led to the ritualization of the table as an altar event with a concomitant reduction of the experience to bread and wine without the meal. The table of the Lord became the altar of the Lord. Without a strong recognition of the Jewishness of the Eucharistic meal, the sanctification of the meal by the cup of blessing and the breaking of the bread was lost and the Eucharistic bread and wine then stood alone independent of a meal context. The meal lost its sanctity and Eucharistic meaning. …

Even though many liturgists assume that the abuse of the table at Corinth was a sufficient reason to separate the Agape from the Eucharist, there is no indication in 1 Corinthians that this was Paul’s intent. Nor did such abuses lead to the elimination of the Agape in the second and third centuries. It appears that the Agape was actually abolished as an act of clerical control over the religious meal and its inappropriateness in the sanctuaries (holy places) of the churches. Whatever value was attached to the Agape was absorbed, in limited ways, by the Eucharistic altar.

[22] H. J. W. Drijvers, “Syrian Christianity and Judaism,” in History and Religion in Late Antique Syria (Aldershot: Variorum, 1994), 124-146.[23] Mazza, The Origins of Eucharistic Prayer. 16-30; J. W. Riggs, “From Gracious Table to Sacramental Elements: The Tradition-History of Didache 9 and 10,” Second Century 4 (1984) 83-101, and H. W. Maria van de Sandt and David Flusser, The Didache: Its Jewish Sources and Its Place in Early Judaism and Christianity (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2002).

I had reached very similar conclusions in my series based on my reading of the evidence. It’s good to know that actual scholars agree.

These conclusions upset the whole “Five Acts” approach to worship. After all, no one can argue with a straight face that we’re actually taking the Lord’s Supper in accordance with the New Testament “pattern.” Rather, we’re taking it in accordance with a pattern that evolved centuries later.

Of course, I’m no patternist, so I see no great sin in our having taken the Lord’s Supper contrary to First Century practice. I just think we’ve accepted second best, that is, table fellowship would be a vast improvement over our token meal because table fellowship builds community. It’s an act of community formation — or we might say “body building.” And it’s more accessible to visitors.

It’s a shame we lost it.

PS — While we’re speaking of the Stone-Campbell Lectures, notice this quote from Scot McKnight, emerging author, Bible scholar, and blogger —

I contend that the Restoration Movement, or the Stone-Campbell movement, made up of the Christian Church and the Churches of Christ, is American evangelicalism’s best-kept secret and, sadly, the most overlooked resource of thinking and praxis. These are Bible people; these are pious people; and there are lots and lots of them; and they are doing excellent work in Bible and theology and church ministry. And neglecting this movement has weakened the robustness of the evangelical voice in the USA.

But, Jay, if historians / scholars agree that the Lord's Supper was taken as part of a love feast in the first century, isn't that evidence of a divinely inspired pattern, which it would be sinful not to follow?

No, on second thought, I think not !!!

What a great example of how CENI advocates pick and choose the examples they wish to impose on their fellow believers.

It's good to hear others realizing that the ceremony we call "the Lord's Supper" is totally unlike the meals which were the practice of both Jewish and Gentile churches in apostolic times. Our practice of having "worship services" is totally unscriptural, yet almost universally the way churches now hold their principal assemblies.

Jay,

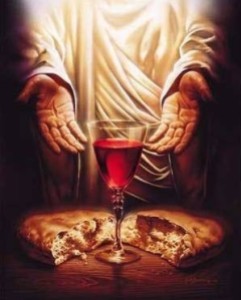

One Cup man here. I like the picture above, One Loaf and One Cup. I think you are becoming a One Cup man!! God Bless!!

There is no evidence that there ever even was an agape meal. The only unambiguous reference to such a thing is in the short epistle of Jude, a book which was still 'disputed' in the 3rd century according to the church historian Eusebius. And why was it 'disputed'? What does that even mean? It means the church of the first 3 centuries was not sure that Jude really wrote it or even that it was written in the 1st century. So, its possible that Jude was written mid to late 2nd century. It can't prove a first century agape meal. The whole concept of the agape meal is all fantasy.

Luther is right. It is a bald-faced lie to say there is a scholarly consensus that the eucharist originally was part of the agape meal. (Claims of scholarly consensus are always suspect.) After all most New Testament scholars do not believe in inerrancy, nor necessarily even in inspiration at least not of the whole New Testament canon. Why then would they all consent to a notion which only exists in Jude, a book not only disputed within the first three centuries of the church as already stated, but also held by many New Testament scholars today to be a fraud created in the 2nd century? You can't count these New Testament scholars in the agape feast eucharist consensus obviously.

Joseph,

Please be more temperate in your comments. I normally put those who call others liars on moderation — because "liar" and "lie" denote an intent to deceive and so is almost always an unfair allegation.

In this case, the person you're calling a liar is not only a scholar, but a very fine Christian known to many of us here and who has a great respect for the inspiration of the scriptures. He's certainly not a liar — and while he might be mistaken, it's unlikely.

And I seriously question any argument that proceeds from a challenge to the inspiration of a canonical book. Even if Jude isn't inspired, it's unquestionably ancient, and so demonstrates the practice of the love feast.

Jude is well attested among the early church fathers — including Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Polycarp, and Barnabas — meaning it was considered authoritative in the early second century.

To say there is no substantion of a "love feast" ignores the context of Pauls' rebuke in his Corinthian letter. Were some filling up on small wafers while others got none? Were some getting drunk on little vials of wine while others went without? What did he chastize them for? For not recognizing the body (church in this case). They were being selfish and ignoring their poorer brothers and sisters. The idea was not that everyone would be stuffed, but that everyone would share. I believe for some in Corinth, this may have been the best meal of the entire week.

In any case the consensus of New Testament scholars in favor of your view is as contrived as the supposed consensus of scientists on global warming.

Has the kingdom of God been reduced to a drink and a meal?

I thought it was more then that.

Mario, there have been several recently who have argued base on that very passage "the kingdom of God is not meat and drink" that we ought not even observe the eucharist anymore. There's also been the theory brought up several times that the eucharist was only meant for Jewish Christians and was abolished with the destruction of the temple and that John's gospel is proof of this since he is the only post-70 writer in the New Testament and his gospel leaves out the institution of the eucharist but instead represents eating Jesus' flesh and blood as belief in him in ch. 6. What should we make of all this? There is an aire of truth to it, since we do see that this meal is the greatest divider of Christianity! What do we do?